Research

Explainable and Diagnosable Machine Learning

I am developing a new framework for diagnosing machine learning algorithms. The methodology allows one to better understand what a machine learned about a particular domain.Multiple View Geometry

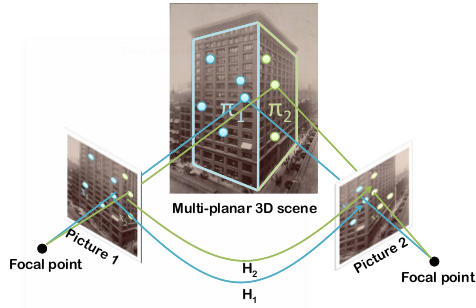

A classic problem in computer vision, called multiple view geometry, is to recover the three-dimensional structure of a scene given several images taken from different vantage points. Working primarily with Wojciech Chojnacki, I am studying various compelling unsolved problems. What makes multiple view geometry so challenging is that the underlying projective models lead to non-linear errors-in-variables parameter estimation problems. Hence Wojciech and I find ourselves working at the interface of various disciplines such as numerical analysis, projective geometry, statistics and computer science.

A classic problem in computer vision, called multiple view geometry, is to recover the three-dimensional structure of a scene given several images taken from different vantage points. Working primarily with Wojciech Chojnacki, I am studying various compelling unsolved problems. What makes multiple view geometry so challenging is that the underlying projective models lead to non-linear errors-in-variables parameter estimation problems. Hence Wojciech and I find ourselves working at the interface of various disciplines such as numerical analysis, projective geometry, statistics and computer science.

We are particularly interested in:

devising new parameter estimation techniques which result in estimates with desirable properties (e.g. unbiased and consistent);

devising new unconstrained optimisation methods which are simpler to implement and faster than established schemes such as Levenberg–Marquardt;

deriving and imposing constraints associated with various mathematical models in multiple view geometry;

creating new constrained optimisation methods which naturally and reliably enforce constraints.

Hence our research endeavours can be characterised as both theoretical and practical.

Ellipse Fitting

Like the circle, the ellipse is one of those primitive geometric shapes that crops up time and time again in many different scenarios. Whether we are tracking an object, calibrating a catadioptric camera or studying cells and crystals, we are bound to end up having to fit an ellipse sooner or later. Surprisingly, fitting an ellipse is actually a hard problem, and much can be learned about more complicated parameter estimation problems in multiple view geometry by studying ellipse fitting.

Like the circle, the ellipse is one of those primitive geometric shapes that crops up time and time again in many different scenarios. Whether we are tracking an object, calibrating a catadioptric camera or studying cells and crystals, we are bound to end up having to fit an ellipse sooner or later. Surprisingly, fitting an ellipse is actually a hard problem, and much can be learned about more complicated parameter estimation problems in multiple view geometry by studying ellipse fitting.

Image Processing at the Limits of Resolution

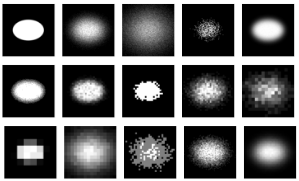

At the limits of camera resolution, objects are blurred, tiny, and almost unrecognisable. To extract relevant knowledge from such limited data, one needs to have some weak prior information about the nature of the object under observation, and a comprehensive mathematical model of the image formation process. The canonical mathematical models of the image formation process make numerous simplifying assumptions which are inadequate when one needs to work at the limit of the sensor resolution. For example, the standard image formation model does not take diffraction and other sources of image blur into account.

At the limits of camera resolution, objects are blurred, tiny, and almost unrecognisable. To extract relevant knowledge from such limited data, one needs to have some weak prior information about the nature of the object under observation, and a comprehensive mathematical model of the image formation process. The canonical mathematical models of the image formation process make numerous simplifying assumptions which are inadequate when one needs to work at the limit of the sensor resolution. For example, the standard image formation model does not take diffraction and other sources of image blur into account.

When working at the limits of sensitivity, one needs to be able to model what happens at the sub-pixel level, and this means that one needs to take the details of the photosensitive area within each pixel into account. Wojciech Chojnacki and I are developing a more sophisticated and tractable mathematical model of the image formation process, which can facilitate precise curve fitting to limited and blurred pixel data. The model incorporates the effects of several elements—the point-spread function, the discretisation step, the quantisation step, and photon noise.